Fertiliser prices have tripled for nitrogen and doubled for phosphorus and potassium. So, what can we do to improve soil fertility and health to reduce inputs and cover some of the rising costs? Independent grassland consultant, Dr George Fisher, gives some pointers.

Having noted the increase in fertiliser nitrogen price at the farm gate, the Radio 4 interviewer of the ‘Today’ programme on May 24, asked the CEO of Yara if fertiliser prices would go even higher. His answer was; “I don’t know”. We seem to be living in a time that’s redefining the parameters of ‘volatility’ and the best we can do is to better manage what is within our control. At the farm level, part of that involves improving nutrient use efficiency, by focusing on soil health and fertility.

Basic soil fertility improves efficiency

A basic nitrogen fertiliser use efficiency on a grassland farm will be round 60%. So, that means for 200kg N/ha from the bag across the season, only 120kg is getting into the grass. By tackling the basics of soil fertility we can raise that efficiency to 80%, or by 40kg N, or £80/ha at current prices. So we need to ensure we have an up-to-date soil analyses done across the farm and target pH 6.5, K (potassium, potash) index 2- and P (phosphate) index 2. We also need to apply 80 to 100kg sulphate per ha on all land, which in itself can raise nitrogen use efficiency by 10%.

The impact of pH can be massive

The graph to the right is from UK research back in the 1980’s, but we need reminding of what we already think we know. This work shows that letting soil pH drop from 6.5 to 5.5, reduces grass growth potential by around 35%. Even at pH 6.0 we can get a 20 to 25% reduction in dry matter production.

Lime sales have soared since the rise in nitrogen costs, but the data proves that trying to save on liming is a false economy.

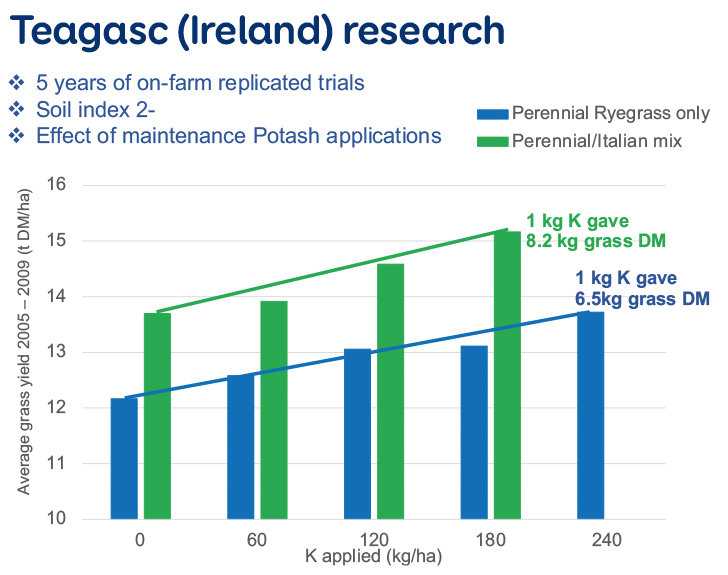

Potash is involved in nitrogen uptake, so it has to be right

Grass takes up nitrogen from soil solution, therefore potassium (potash) is critical to that process. Even when we are at the target soil fertility of K index 2-, we need to make sure that maintenance applications are going on. This was shown through work in Ireland by Teagasc (see graph below), where applying up to 240kg potash/ha gave a 6.5 to 1 return in grass dry matter in perennial ryegrass and 8.2 to 1 on Italian/perennial ryegrass mixes.

Grass takes up nitrogen from soil solution, therefore potassium (potash) is critical to that process. Even when we are at the target soil fertility of K index 2-, we need to make sure that maintenance applications are going on. This was shown through work in Ireland by Teagasc (see graph below), where applying up to 240kg potash/ha gave a 6.5 to 1 return in grass dry matter in perennial ryegrass and 8.2 to 1 on Italian/perennial ryegrass mixes.

Phosphate response

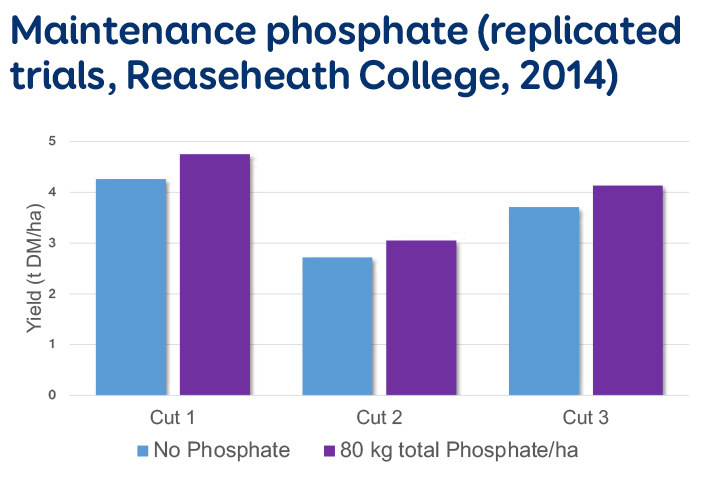

Similar effects to the potash Teagasc studies were seen in work at Reaseheath College (graph below). On an index 2 sandy clay loam soil, making sure a three cut silage system got the maintenance phosphate it needed raised yield from 10.7 to 11.9 t DM/ha, a 15 kg grass dry matter return for every 1kg phosphate added. Not surprising when we consider that phosphate is crucial for root health and energy transformation in photosynthesis.

Similar effects to the potash Teagasc studies were seen in work at Reaseheath College (graph below). On an index 2 sandy clay loam soil, making sure a three cut silage system got the maintenance phosphate it needed raised yield from 10.7 to 11.9 t DM/ha, a 15 kg grass dry matter return for every 1kg phosphate added. Not surprising when we consider that phosphate is crucial for root health and energy transformation in photosynthesis.

Don’t forget sulphur

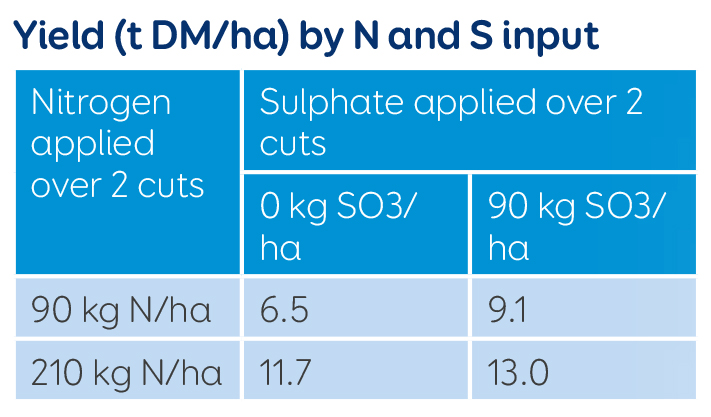

As nitrogen prices have gone up, many farmers try to keep costs down by buying straight N fertilisers without sulphur in them. This is another false economy. Even at the prices we are dealing with, the cheapest feed on farm is still grazed or cut grass and on most soils we can’t get enough sulphur (S) from soil reserves and manure inputs, to support nitrogen uptake (efficiency) and grass growth. The table below shows this in stark reality for a two cut system trial run by SRUC in Aberdeen in 2018.

As nitrogen prices have gone up, many farmers try to keep costs down by buying straight N fertilisers without sulphur in them. This is another false economy. Even at the prices we are dealing with, the cheapest feed on farm is still grazed or cut grass and on most soils we can’t get enough sulphur (S) from soil reserves and manure inputs, to support nitrogen uptake (efficiency) and grass growth. The table below shows this in stark reality for a two cut system trial run by SRUC in Aberdeen in 2018.

Yield on the same sward doubled when the recommended rates of N and S were applied. At the 210 kg N/ha rate (derived from the Fertiliser Manual, RB209), the return on S input was 14 kg grass dry matter for every kg sulphate applied.

Manure – from brown to gold

We need to appreciate that most of the nutrients in our slurry and FYM come from the manufactured fertiliser and feeds that we buy-in, so we have already paid for them. Manures are not a waste to be disposed of, they are a recycling asset to be managed.

The starting point for managing this asset is to know what nutrients it contains. There is no logic in complaining about fertiliser and feed prices by not knowing the nutrient content of our manures. Sampling to get an analysis is a messy and unattractive job, but is definitely worthwhile.

A study by ADAS, who analysed over 500 slurries, revealed just how variable the nitrogen content of slurries can be. The Fertiliser Manual uses a value of 2.6 kg N/m3 of slurry for a 6% dry matter material as an average and the ADAS work showed this to be correct, as an average. But the range went from 1.2 to 4.5 kg N/m3. By definition, only about 25% of farms will have an ‘average’ slurry; it depends on the system you operate and how you store the material. So, getting an analysis done and using it to make sure you are only putting on what you need from bagged nitrogen can pay handsomely. For example, if your slurry is 3.6 kg N/m3, rather than the book value of 2.6, this represents an extra 40 kg available N/ha from your slurry rather than the bag for a stocking rate of 2.5 cows/ha.

We also need to look at when, how and where we are applying slurry nutrients. Switching as many applications as we can from autumn and winter to in-season and also moving from splash-plate application to dribble-bar, or even injection, can help. It’s about the accumulation of small gains, and adding these two changes together could remove 20 to 40kg N/ha of brought-in fertiliser applications.

For most cattle systems, the maintenance phosphate and potash we need will come from slurries and manures, as long as we are spreading them across the farm. So, when it comes to where we are applying manures, we need to check our soil analyses and make sure that fields with lower fertility (generally those away from the steading) are getting their input from manures. It is a pain to haul slurries and manures further from the core of the farm, but is cheaper than buying those nutrients in a bag to get the benefits of a properly balanced soil fertility and fertiliser plan.

Dig for victory (soil health)

Soil fertility is really ‘soil chemistry’. But we also need to consider soil health in the ground, which includes soil structure (physics) and bugs (biology). All three are inextricably linked but the only way to assess the structure and biological health of your soil is to get out with a spade and dig inspection pits.

Healthy soils have a profile that has minimal compaction. This allows air into service the bugs and water to flow through, rather than run off or sit on the surface. Sounds simple, but it’s really important. Well-structured soils dry out more quickly in spring and wet up more slowly in the autumn, allowing more grazing on the shoulders of the season. Extending grazing through good soil structure can be worth £2.50 to £3.50 per cow per day, according to SRUC and AHDB Dairy, in reduced feed and labour costs – that’s £3,500 to £4,900 per week for a 200 cow herd.

Getting soil structure right is the basis of the whole job. By reducing compaction, or restoring compacted soils, the biology and organic matter of the soil will work better and it’s those worms and bugs that turn over the organic nutrients in manures, making them available for grass growth and replacing bought-in fertilisers. More grass gives us the opportunity to reduce bought-in feeds.

The useful thing about focusing on soil fertility and health is that everything is connected. You improve one aspect, such as soil structure, and other things like nutrient availability from slurries, will follow.

So, our response to not knowing what the future price of fertilisers will be? Well, partly it’s to control the health of our assets so that we don’t have to buy so much. And doing this means we grow more energy and protein at home, reducing feed costs, which is another unknown factor going forward.